Haunted — By Lucy McBee

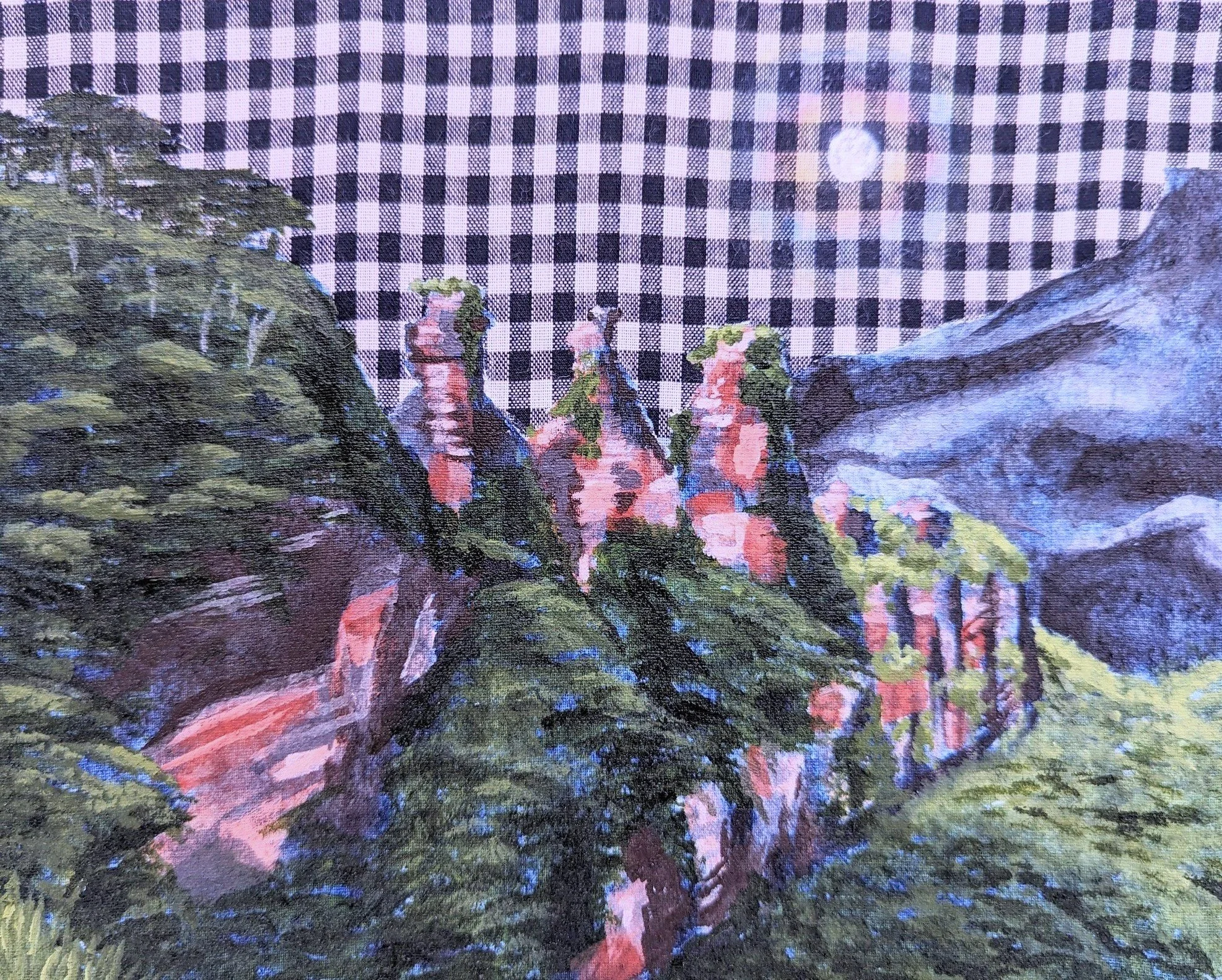

artwork by Sonia Redfern

My grandson, who is four, is preoccupied with haunted things.

It started with an old service truck entombed in chin-high weeds alongside abandoned railroad tracks behind the automotive shop where his father works. He calls it an ice cream truck, but there’s no way to know this. Paint eaten by rust, any sign of branding is long gone. True, there’s a window where a vendor might lean out and pass a tippy-toed kid a cone like a sputtering torch. But it could’ve also been a taco truck or a catering truck or something less inspiring. A plumbing supply truck.

When I asked him what he thinks being haunted means—after all, he might have only a phonetic grasp on the word—he said it’s where ghosts live and it’s scary and he doesn’t want to think about it.

And yet, he’s obsessed with (not) thinking about it.

Unswayed by arguments that it doesn’t belong to us, he wants his dad to fix the truck. Chase off squatter squirrels, replace gnawed wires, sweep away droppings and dust and decay, fit it with a new engine and glaze it with fresh paint, stock it with strawberry ice cream and chocolate sprinkles. And, finally, install the loudest, cheeriest bell, one that draws a bright line in the atmosphere, impossible for ghosts to cross.

#

My son was twenty-three when he died in prison. I don’t know if the family was presented with an option other than cremation; I was in no shape to make decisions. My ex-husband refused the ashes. He was angry with our son for abandoning the kind of life we raised him to inhabit, and finally, for abandoning any kind of life at all. I didn’t refuse, nor did I accept. I was broken and unmoored. In body, I was 1,827 miles away, but in mind, I was in that cell.

My son’s ex-girlfriend, who wouldn’t have been an ex if it had been up to her, claimed his ashes before the discard deadline and kept them safe for us should we ever want them.

Eventually, my daughter did. She bought an urn. Hunter green, her brother’s favorite color. She didn’t trust herself to transfer the ashes from box to urn, and the same ex-girlfriend told her that any funeral home would do it for her.

I wonder if that ex-girlfriend kept any for herself, and if they haunt her, unsettled, apart from the rest.

#

Now, when I’m choosing a new library book for my grandson, he asks me to be sure there aren’t any ghosts in it.

I flip through and tell him it’s all clear.

“But ghosts know how to hide when you’re looking for them,” he says. “You better check again.”

#

My daughter went to the nearest funeral home, the one with a lawn sign in flowery script, ringed by marigolds. As if it were a place for beginnings. She didn’t say much about the experience, other than the employee was a woman, and the transfer was done out of her sight. Now that I think about it, I didn’t ask for details. How did the place smell? How did she treat you? What was her demeanor like? How long did you wait? How did the urn feel with your brother’s ashes inside? Did she dispose of the box—stamped with his inmate number—in the backroom, or did she present it empty and ask whether you wanted it?

Did you cry?

#

Twice a week, I collect my grandson from preschool. Spring is the time for new beginnings! shouts the classroom poster. We are forced to drive past that same funeral parlor. Every goddamned time. It’s impossible to avoid it and still get home.

From his carseat in the back, he points out garbage trucks and flatbeds and tow trucks and comments on where they fall on the dirty/clean spectrum. If we need to stop at his father’s shop, the conversation gets hijacked by the haunted ice cream truck, sulking behind its shroud of stalks and leaves. How next time maybe I’ll let him get closer, maybe even step into the weeds. Maybe even tap a rusty fender. And how he doesn’t like holding hands, but he’ll hold my hand for that.

Obviously, I do not point out the funeral home, nor do I say what I’m thinking as we pass, how people can be in two places at once. And how hauntings don’t always involve ghosts.

#

My daughter sent me the Amazon link so I could buy a matching urn. Once I’d moved back to the East Coast from Austin, we visited the funeral home together.

It smelled citrusy. The same woman who’d helped my daughter two years prior greeted us. She was attentive and gentle and kind. Cradling both urns, she disappeared into the back. We didn’t wait more than eight or nine endless minutes, sitting on the stiff sofa while linking hands (her right in my left), guarded by Kleenex boxes. With the ashes inside, the urn felt impossible. A new appendage. I knew which was mine because it wasn’t dusty and had a sticker on the bottom, but the helpful person differentiated them anyway.

In the car, in the parking lot, we cried.

#

While we’re driving past the funeral home, the boy—who never met the person who would’ve been his living, breathing, wildly funny, ever-more-surprising uncle—asks if we can go to Dairy Queen. His voice, bright and undimmed, is the dearest thing I know. Just then I’m scared that my need for him to be here for a very long time—long past mine—will haunt him, and if I don’t strip the terror from my voice, the haunting can never be undone. I try to fully inhabit the world inside this car, instead of what passes away as we edge forward.

“Yes,” I say. “Yes, honey, let’s get some ice cream.”

Lucy McBee is a ghostwriter and editor based in central Connecticut. She is the nonfiction winner of the 2024 Iowa Review Award. Additionally, her (non-ghostwritten) work has appeared in Indiana Review, New Letters, and The Pinch.